The Low-Back Outcome Scale and the Oswestry disability index: are they reflective of patient satisfaction after discectomy? A cross sectional study

Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a major cause of low back and leg pain. It imposes a heavy cost burden on both the individual patient and on society (1). It is a common indication for lumbar spine surgery (2). There are several tools such as the Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire (JOABPEQ) (3), the Oswestry disability index (ODI) (4), the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) (5), and the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) (6), for measuring performance status or functionality in these patients. On the other hand, patient satisfaction is believed to be an attitudinal response to value judgments that patients make about their clinical experience and is associated with many variables, such as patient demographics, symptom-related expectations, functional status, mental disorders, unmet expectations, doctor–patient communication, and to a large extent, patient expectations (7).

Prior studies have shown that discectomy is a safe and effective surgical technique for the treatment of LDH based on various measures (2,8). However, little is known about the correlation of patient satisfaction to functioning status after surgical treatment for LDH (9). In addition, in some cases, spine surgeons and patients occasionally do not agree on the success of the treatment. The main question is: Does the tool reflect the true value of patient satisfaction following discectomy? Moreover, in the literature, there has been a trend toward the assessment of patient satisfaction as an outcome measure (10-15). Hence, this study was performed to compare the Low-Back Outcome Scale (LBOS) of Greenough and Fraser and ODI with patient satisfaction in a prospective study over a 2-year period.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross sectional prospective study in order to assess outcome measures in a group of patients with LDH. Patients were completed the study measures at two points in time: baseline (before surgery) and two years post-surgery assessments (follow-up).

Setting

The study was carried out in a clinic of a teaching hospital affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Data were collected from June 2009 to October 2013.

Participants

All patients who underwent discectomy with a single-level disc herniation were eligible to be included in the study. The diagnosis of LDH was made on the basis of clinical and radiographic evidence. All participants underwent a complete clinical examination for LDH including an assessment of clinical symptoms and clinical examination, and imaging studies including plain radiography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine. In all cases more than one spine surgeon confirmed the diagnosis and experienced surgeons performed surgery. There were no restrictions on patient selection with regard to level(s) of LDH, age or other characteristics. We excluded all patients with previous back surgeries, malignancy, fracture, spinal cord compression, and spinal anomalies from the study.

Operative procedure

Standard open lumbar discectomy was used to manage LDH in patients who have persistent symptoms of the condition that do not improve with a conservative treatment (16).

Outcome

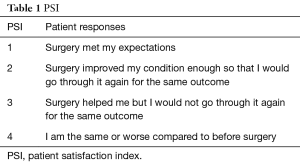

The study outcome was patient satisfaction post discectomy. Patient satisfaction was assessed by the patient satisfaction index (PSI). The PSI was completed for each patient by face-to-face interview. A PSI response of 1 or 2 was considered to be associated with a satisfied outcome and a PSI response of 3 or 4 to be associated with a dissatisfied outcome (Table 1) (17).

Full table

Additional measures

- The Finneson-Cooper score was also used. This is a lumbar disc surgery predictive score card or questionnaire that was developed by Finneson-Cooper to evaluate potential candidates for excision of a herniated lumbar disc (18). The Finneson-Cooper score ranges from 0 to 100. It categorizes candidates into a 4-grade classification: good >75; fair 65–75; marginal 55–64, and poor <55. The Finneson-Cooper score was measured at preoperative.

- The LBOS of Greenough and Fraser was used for measuring functional outcome in patients with low back pain. The LBOS scale ranges from 0 to 75 and the higher score indicates better condition. It categorizes patients into a 4-grade classification scheme: excellent ≥65; good 50–64; fair 30-49, and poor 0–29 (19). In this study excellent and good classification were considered satisfied and fair and poor classification were considered dissatisfied. The LBOS was measured at last follow-up.

- The Iranian version of ODI (Version 2) is a measure of functionality and contains 10 items. The scores on the ODI range from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating a worse condition. The psychometric properties of the Iranian version of questionnaire are well documented (4). The ODI score was measured at admission and at last follow-up to assess functionality outcome after treatment. A minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is a threshold used to calculate the effect of clinical treatments. Satisfied was defined as a 13-point improvement from the baseline ODI scores (20).

- Demographic information including age, gender and body mass index (BMI), a leg pain visual analog scale (VAS) and a VAS associated with back pain also were collected. The duration of symptoms (in months), type of herniation and smoking histories were assessed.

Bias

Certain cases may have been incorrectly classified and thus affecting the results.

Sample size

Based on at least 20% failure rate for surgery we estimated that a sample of 152 patients would be enough to have a study of 80% power at 5% significant level. However, we recruited 163 patients for the study.

Statistical analysis

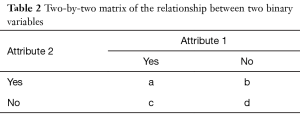

First, patients were classified using the LBOS, the ODI and the PSI classification. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the findings. The phi coefficient was estimated to assess the correlation between the PSI and the ODI; the PSI and the LBOS. In fact, the phi (Φ) is a measure of the degree of association between two binary variables and is similar to the correlation coefficient in its interpretation. The Φ for a 2×2 table could be calculated as in Table 2.

Full table

If a, b, c, and d represent the frequencies of observations, then Φ is determined by the following relationship

Φ = (ad – bc)/√{(a + b)(c + d)(a + c)(b + d)}

Φ is always between −1 and +1. Correlations with Φ coefficients of >|0.7| are strong, the ones with coefficients of |0.5|–|0.7| are medium, and the ones with <|0.5| weak. The significance of Φ might be tested by determining the value of chi-square (χ2) (21,22).

All statistical analyses were performed using the PASW Statistics 18 Version 18 (SPSS, Inc., 2009, Chicago, IL, USA). A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The reference points for this study were the date of the initial surgery. The primary end points for the statistical analysis were at least 2-year of follow-up.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

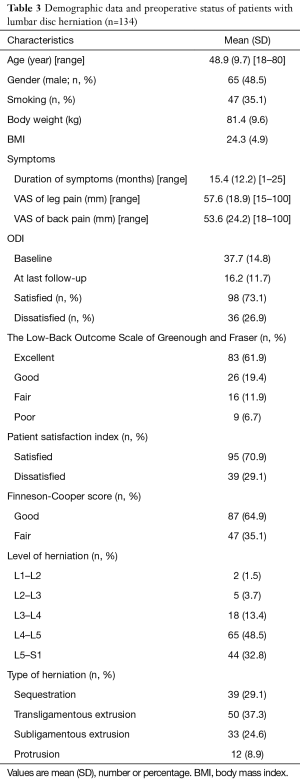

In all 163 patients were entered into the study. Of these, the data for 134 patients (65 men and 69 women) were available for analysis. Eleven patients were excluded because of deficient follow-up data, two patients due to recurrent disk herniations, and 16 cases due to malignancy, fracture, spinal cord compression, and spinal anomalies. The characteristics of patients are shown in Table 3.

Full table

Descriptive data

In all 80 patients underwent discectomy via laminotomy and the remaining 54 patients received fenestration, no case was observed with missed level surgery. Cauda-equina syndrome occurred in one case (0.7%). In one case (0.7%) dural laceration occurred during surgery which were repaired and no one showed CSF leakage or meningitis. No mortality rate was observed due to surgery. Patients scores on the PSI, the Finneson-Cooper score, the ODI and the LBOS are shown in Table 3.

Outcome data

Based on the PSI, the ODI and the LBOS, post-surgical satisfactions were 95 (70.9%), 98 (73.1%) and 109 (81.3%), respectively. Mean improvement in the ODI was 21.5±12.1 and statistically was significant (P<0.001) at 2-year follow-up. No significant differences were observed for post-surgical satisfaction between levels of LDH.

Main results

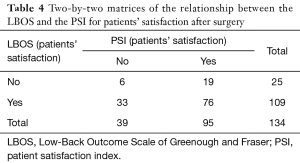

To determine patients’ satisfaction correlation analysis was carried out. There were weak associations between PSI and LBOS (Φ=−0.054, P=0.533; χ2=0.388, P=0.533); PSI and ODI (Φ=−0.129, P=0.136; χ2=2.22, P=0.136). The results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

Key results

To the best of our knowledge, no published study has investigated whether the ODI and the LBOS reflects true patient satisfaction after discectomy. We demonstrated a limitation for the ODI and the LBOS as an outcome measure in reflecting patient satisfaction. In general, such measures have their own limitations and depending on their development history might give different profile from one to another scale for one identical patient. These measures usually are developed based on a classical test theory (CTT) where psychometric properties for an instrument does not include difficulties that one might experience in responding to each question. However, more recent patient-reported outcomes are those that do not assume that each item is equally difficult [item response theory (IRT)]. The IRT treats the difficulty of each item as information to be incorporated in scaling items (23).

Interpretation

The LDH surgery is a successful operation in majority of patients. In most patients the pain in the affected leg disappears almost immediately. However, in 10–40% of patients the symptoms either do not disappear or recur. In spite of this high symptom recurrence rate, it is reported that almost 90% of patients are satisfied with the operation according to the variety measures and the various follow-up assessments (9). In this study, based on the PSI, the ODI and the LBOS, post-surgical satisfactions were 70.9%, 73.1% and 81.3% at 2-year follow-up, respectively. These observations indicate that we must seek means to improve prognostication prior to member spine surgery; i.e., we need to develop a better decisions-making and strategic planning process (9,24).

We found that the ODI and the LBOS lacked significant association with the PSI to determine patient’s satisfaction. Hence, these measures are not reflective of true patient satisfaction after discectomy. There is a risk of underestimating patient satisfaction after discectomy based on lower levels of scores on the LBOS and the ODI measures, and there also is a risk of overestimating patient satisfaction based on higher levels of scores on the LBOS and the ODI measures. This finding could be attributed to the influence of patients’ expectations, other factors that improve satisfaction without improving outcome measures as home support visitors, functionality status, level of herniation, surgical procedure type, and preoperative counseling, in patients with LDH (25). The literature has shown that, among other factors, patient expectations regarding surgery influence satisfaction with treatment. It has also been shown that such expectations can be altered by the information that is transmitted by the surgeon (15,26). Gepstein et al. reported that preoperative expectations correlated with postoperative satisfaction rate in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (27). To determine patient expectations in lumbar spine surgery, Toyone et al. reported that, even if the clinical expectations were met, some patients remained dissatisfied (26). Godil et al. showed that patient satisfaction is not a valid measure of overall quality or effectiveness of surgical spine care (15). In addition, patient satisfaction was evaluated with a dichotomous yes/no question and may not fully represent this aspect of outcome in patients with LDH. Based on the aforementioned, it is clear that a standardized metric or objective assessment tool for comparing techniques or treatments is needed.

One might inquire about the need to investigate relationships between satisfaction and quality of care. Certainly, satisfaction and quality of care are very different terms, with very different meanings (15,28). In addition, there is no doubt that the use of patient satisfaction scores represents an important target for the treatment of patients with low back pain. Moreover, patient satisfaction tools alone should not be used to represent the overall quality, safety, or effectiveness of surgical spine care (15). However, researchers have suggested that we should examine our own patients’ satisfaction scores and seek to improve them. This may lead to an improved decision-making process for the patient (28,29).

Limitations

Although prospective, there were still limitations to this study. Firstly, this study was associated with a relatively small sample size for dissatisfied patients (n=35). Secondly, this study only included patients from a single institution. Thirdly, this study did not have a control group and no short-term follow-up. Fourthly, this study did not investigate the differences between long- and short-term follow-up of surgical satisfaction of LDH patients. Fifthly, this study did not investigate all factors influencing a satisfaction measures in LDH patients. We believe that satisfaction also might be associated with depression and psychological distress, gender differences, lower educational attainment, unmarried status, low social support, unemployment, lack of health insurance, presence of a major medical condition, poor adverse health-related behaviors (smoking, alcohol use), fatigue, altered sleep, low self-efficacy, poor pain coping strategies, somatization and ethnic and racial differences (28). Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate these parameters. Finally, due to the above-mentioned limitations, we believe the results should be interpreted with caution and one should not generalize the findings. Above all, we believe the best way to avoid these is to develop a standardized method for evaluation of patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that the ODI and the LBOS as outcome measures do not reflect patient satisfaction after discectomy. Further work is needed in this arena to assess other factors that improve satisfaction without improving outcome measures that may influence patient satisfaction after discectomy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Neurosurgery Unit at Imam-Hossain Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The Ethics Committee of Shahid-Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, Pampati V, et al. Cost utility analysis of caudal epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation, axial or discogenic low back pain, central spinal stenosis, and post lumbar surgery syndrome. Pain Physician 2013;16:E129-43. [PubMed]

- Strömqvist B, Fritzell P, Hägg O, et al. Swespine. the Swedish spine register: the 2012 report. Eur Spine J 2013;22:953-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azimi P, Shahzadi S, Montazeri A. The Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire (JOABPEQ) for low back disorders: a validation study from Iran. J Orthop Sci 2012;17:521-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, et al. The Oswestry Disability Index, the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine 2006;31:E454-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azimi P, Mohammadi HR, Montazeri A. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with lumbar disc herniation: a validation study of the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score. J Orthop Sci 2012;17:341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi HR, Azimi P, Zali A, et al. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with low back disorder: A validation study of the Iranian version of Core Outcome Measures Index. Asian J Neurosurg 2015;10:46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Zhang D, Ma L, et al. Factors Predicting Patient Dissatisfaction 2 Years After Discectomy for Lumbar Disc Herniation in a Chinese Older Cohort: A Prospective Study of 843 Cases at a Single Institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1584. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:2441-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verbeek JH. Patient satisfaction following operation for lumbosacral radicular syndrome: an apparent paradox. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005;149:1493-4. [PubMed]

- Bair MJ, Kroenke K, Sutherland JM, et al. Effects of depression and pain severity on satisfaction in medical outpatients: analysis of the Medical Outcomes Study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2007;44:143-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kane RL, Maciejewski M, Finch M. The relationship of patient satisfaction with care and clinical outcomes. Med Care 1997;35:714-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:405-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA, Meterko M, et al. Mental illness as a predictor of satisfaction with inpatient care at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:680-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal MB, Fernandopulle R, Song HR, et al. Paying for quality: providers' incentives for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:127-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Godil SS, Parker SL, Zuckerman SL, et al. Determining the quality and effectiveness of surgical spine care: patient satisfaction is not a valid proxy. Spine J 2013;13:1006-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garg B, Nagraja UB, Jayaswal A. Microendoscopic versus open discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective randomised study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011;19:30-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Slosar PJ, Reynolds JB, Schofferman J, et al. Patient satisfaction after circumferential lumbar fusion. Spine 2000;25:722-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finneson BE, Cooper VR. A lumbar disc surgery predictive score card. A retrospective evaluation. Spine 1979;4:141-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azimi P, Nayeb Aghaei H, Azhari S, et al. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with low back disorder: a validation study of the Iranian version of Low Back Outcome Score. Asian Spine J 2016;10:719-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Copay AG, Glassman SD, Subach BR, et al. Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study questionnaire Short Form 36, and pain scales. Spine J 2008;8:968-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- PHI COEFFICIENT. Available online: http://documents.mx/documents/phi-coefficient.html. 2016

- Kirkwood BR, Sterne JA. editors. Essential Medical Statistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004.

- Cappelleri JC, Jason Lundy J, Hays RD. Overview of classical test theory and item response theory for the quantitative assessment of items in developing patient-reported outcomes measures. Clin Ther 2014;36:648-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1829-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, et al. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:947-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toyone T, Tanaka T, Kato D, et al. Patients’ expectations and satisfaction in lumbar spine surgery. Spine 2005;30:2689-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gepstein R, Arinzon Z, Adunsky A, et al. Decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in the elderly: preoperative expectations and postoperative satisfaction. Spinal Cord 2006;44:427-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Truumees E. Appropriate use of satisfaction scores in spine care. Spine J 2013;13:1013-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daubs MD, Norvell DC, McGuire R, et al. Fusion versus nonoperative care for chronic low back pain: do psychological factors affect outcomes? Spine 2011;36:S96-109. [Crossref] [PubMed]