Multimodal analgesia in pain management after spine surgery

First described by Kehlet and Dahl in 1993, multimodal analgesia (MMA) is the simultaneous use of multiple analgesic medications that work in a synergistic manner, providing pain control while mitigating the adverse effects of each individual drug due to lower dosages (1,2). Pain management in today’s practice has progressed to also encompass preoperative patient education, intraoperative anesthesia, and postoperative care. In the realm of orthopedic surgery, adult reconstruction has seen the widespread popularity of MMA in the management of postoperative pain (3). Patients who underwent total hip and knee arthroplasty have reported a significant reduction of pain, narcotics consumption, and length of hospital stay after receiving MMA (4). In fact, there has been a shift from the inpatient to the outpatient ambulatory setting for patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty owing to the combination of increasing utilization of minimally invasive surgical techniques, enhanced postoperative recovery, and implementation of MMA protocols (5).

Similarly, spine surgery has also seen the growth and establishment of multimodal perioperative protocols for managing pain (6-8). Postoperative pain following spinal procedures is a common complaint, with persistent pain even after the immediate convalescent period leading to negative impacts on physical, social, and emotional health (9). On the other hand, sufficient pain management can lead to favorable outcomes such as superior mobility and coordination, quicker recovery, lower risk of complications, and greater patient satisfaction (10-12). Pain control following spine surgery has traditionally utilized opioid medications administered intermittently on an as-needed basis in response to pain. However, interval provisions of narcotics may lead to opioid-related side effects such as tolerance, cardiovascular and respiratory depression, altered mental status, diminished wound healing, and urinary retention, among others (13). In response, a preemptive MMA regimen, or analgesia provided before the onset of pain, has been developed to mitigate the activation of central neurons and the subsequent exaggerated response to pain by neurons in the periphery (14).

A paradigm shift from the traditionally open to minimally invasive techniques in spine surgery (MIS) has been made possible by technological advancements (15). Open approaches to spine procedures can result in significant intraoperative and postoperative morbidity due to the utilization of large incisions and greater extent of damage to the soft tissues and structures from dissection and retraction (15). On the other hand, decreased surgical duration, intraoperative blood loss, shorter postoperative inpatient stay, and faster recovery following surgery can be achieved by virtue of the narrow incisions and limited tissue trauma sustained during MIS spine procedures (16). MIS procedures have also demonstrated improvements in postoperative pain and decreased narcotics consumption when compared to open techniques (15). Nevertheless, any persistent pain, discomfort, or disability following MIS surgery can contribute to delayed recovery and function (17). Recent evidence also suggests that acute postoperative pain is an important predictor for chronic pain after surgery (18). As such, a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates help from all members of the healthcare team, including the nursing staff, anesthesia services, and postoperative rehabilitation providers, will be essential in reducing morbidity and complication rates following MIS spine surgery (19).

Prior investigations have demonstrated that postoperative pain following spine surgery may involve multiple pathways including neuropathic, inflammatory, and nociceptive pain responses (20). Post-surgical pain has been determined to be directly related to the number of vertebral levels on which the operation took place, regardless of the spine region involved (21). Surgical incision has been implicated in the etiology of postoperative pain through activation of the inflammatory response resulting from tissue damage at the cellular level (22). Response to injury manifesting as cardinal signs of inflammation such as pain, edema, erythema, and fever are induced by local activation of prostaglandins (23). In turn, this can lead to the overstimulation of peripheral nociceptors, causing an acute pain response known as primary hyperalgesia (24,25). Previous studies have evaluated the major prostaglandins, cytokines, and interleukins (ILs) that play a major role in the induction of the acute pain response, determining prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2) and IL-6 to be the among the predominant agents that induce pain and inflammation (25,26). For instance, a study by Buvanendran et al. determined there to be an increase in the concentration of PGE-2, IL-6, and IL-8 in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid within the first 30 hours after a total hip arthroplasty procedure (22). The severity of inflammation was found to be correlated with the local concentration of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which stimulates the initial release of IL-6 from various cell types at the site of injury, including endothelial and epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and monocytes (25).

The subsequent development of chronic pain can result from activation of the N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and prolonged stimulation of the central nervous system, a process known as central sensitization or secondary hyperalgesia (22,23). The ensuing neuroplastic changes that lead to long-term potentiation of pain result from the production of cyclooxygenase (COX) and nitric oxide synthase (NOS), which in turn upregulate prostaglandin synthesis (24). In this context, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that work by inhibiting the COX pathway and decrease the production of prostaglandins can directly reduce inflammatory fever and pain (20). A meta-analysis of ten studies conducted by Jirarattanaphochai et al. determined that the combined use of NSAIDs and opioid medications following spinal procedures such as discectomy or laminectomy led to decreased total amount of narcotics consumed and postoperative pain when compared to the sole use of opioid medications (27). This finding adds to the growing body of knowledge that the use of pharmacological agents which simultaneously act upon multiple pain pathways can provide a synergistic effect, allowing for reduced amounts of each individual medication utilized and the associated dose-related side effects. However, it is important to note some evidence in the literature suggests NSAIDs that inhibit COX-2 are associated with diminished fusion rates and bone healing (28-30). For instance, while low to normal doses of NSAIDs provided decreased postoperative pain and narcotics consumption without adverse effects, high-dose NSAIDs typically reserved for treating severe pain were associated with higher rates of pseudarthrosis (31). Therefore, it may be advisable for the spine surgeon to practice caution when prescribing NSAIDs for pain management following spinal fusion procedures.

By demonstrating decreased consumption of narcotics and shorter hospital length of stay, preemptive analgesia protocols in MIS spine surgery have proven to be an effective form of pharmacological intervention that targets the nociceptive receptors in addition to inhibiting the inflammatory pathway (20). For example, the preoperative administration of 600–1,200 mg of gabapentin or 100–150 mg of pregabalin several hours prior to surgery resulted in decreased pain and narcotics consumption on postoperative day 1, as well as reduced likelihood of breakthrough pain from occurring (32,33). Providing 1–2 g of acetaminophen preoperatively has also led to a reduction of morphine required to control postoperative pain (20). Preemptive MMA that combined 75 mg of pregabalin, 500 mg of acetaminophen, 200 mg of celecoxib, and 10 mg of extended-release oxycodone 1 hour before surgery resulted in lower patient reports of pain scores postoperatively when compared to the singular administration of intravenous (IV) morphine (34). Because the nociceptive pain response sustained from surgical trauma is usually localized, temporary, and often improves with time, therapeutic measures delivered intraoperatively or in the immediate postoperative setting can also be effective. For instance, the preoperative distribution of local anesthetics such as lidocaine and epinephrine into the soft tissue surrounding the incision site, followed by wound closure with 30–40 milliliters of 0.5% ropivacaine were found to decrease postoperative pain and narcotics consumption (35,36). Postoperative administration of epidural analgesia also demonstrated improvement of pain, decreased narcotics consumption and postoperative nausea, and faster recovery of bowel function following spine procedures (37,38).

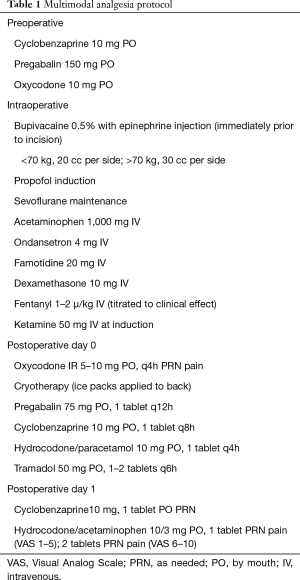

A review of the literature reveals a variety of different MMA protocols utilized by spine surgeons, and the optimal pain management technique remains a topic of continued research. For instance, Singh et al. (the senior surgeon of this review) conducted a retrospective review of 139 patients undergoing a l-level minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MIS TLIF) procedure followed by either MMA or patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) protocols (39). Outcomes including patient-reported pain scores in the inpatient setting, narcotics consumption after hospital discharge, duration of hospital stay, surgical complication rates, and opioid-related adverse effects such as postoperative urinary retention and nausea/vomiting were compared between the MMA and PCA cohorts. The MMA protocol, detailed in Table 1, was developed through a collaboration between surgeons and anesthesiologists at our institution. Patients who received MMA demonstrated lower rates of inpatient narcotics consumption, nausea/vomiting, and a reduced duration of hospital stay. However, there were no differences in postoperative narcotics consumption after hospital discharge, inpatient pain scores, or urinary retention. These findings suggest MMA provides comparable pain control to PCA while allowing for a reduction of inpatient narcotics consumption, which in turn may lead to decreased nausea/vomiting and duration of hospital stay. A related review of anesthetic and analgesic techniques for MIS spine surgery by Buvanendran et al. recommended the preoperative implementation of MMA before surgery takes place (40). The article also highlighted the importance of being judicious about precluding patients that may not be suitable candidates for receiving expedited pain protocols in conjunction with same-day MIS spine procedures. Given the challenges associated with the continuous infusion of IV opioid therapy in these “fast-track” MIS spine patients, one potential alternative is the use of low-dose intraoperative ketamine (an NMDA antagonist), which has been demonstrated to decrease postoperative narcotic requirements (41). Lastly, other investigations in the literature have demonstrated additional benefits of MMA, including quicker return to mobilization, shorter hospital stay, and reduced opioid-associated side effects such as constipation, respiratory depression, somnolence, nausea, and vomiting (17,42).

Full table

With rising healthcare costs and increasing emphasis being placed on value-based care in recent years, there has been a movement toward reducing the duration of hospital stay without sacrificing the quality of care delivered to patients (43). As such, growing numbers of MIS spine procedures are being performed in the ambulatory setting with the expectation that discharge will occur on the same or next day. This requires a concomitant dedication to optimizing a safe and effective analgesic protocol that provides adequate pain control, minimizes side effects, and can easily be managed by either the patients themselves or their caretakers even after discharge from the surgery center (44). The conventional use of IV-administered, opioid-based PCA protocols are thus not a reasonable option for pain management following spine surgery in an outpatient center. Additionally, unintended adverse effects of anesthetic and analgesic medications such as insufficient pain control, intractable nausea and vomiting, gastrointestinal and bladder dysfunction, and altered mental status are all factors that can hinder discharge from taking place on the day of surgery (45). MMA protocols successfully implemented by a multidisciplinary team offer a promising solution for reducing postoperative pain and narcotics dependence in patients undergoing MIS spine surgery in the outpatient setting. As summarized in our review, there is a growing body of knowledge that demonstrates the efficacy in the combined use of opioid-alternative medications such as NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, local anesthetics, acetaminophen, and other neuromodulatory pharmacologic agents. Moving forward, continued research will be essential in the optimization of the MMA protocol for treating patients who undergo ambulatory MIS spine procedures.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg 1993;77:1048-56. [PubMed]

- Wall PD. The prevention of postoperative pain. Pain 1988;33:289-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buvanendran A, Tuman KJ, McCoy DD, et al. Anesthetic techniques for minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2006;19:133-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari AV, Blum YC, Shekhar L, et al. Multimodal pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty at the Ranawat Orthopaedic Center. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1418-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berger RA, Sanders SA, Thill ES, et al. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1424-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurd MF, Kreitz T, Schroeder G, et al. The Role of Multimodal Analgesia in Spine Surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2017;25:260-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Devin CJ, McGirt MJ. Best evidence in multimodal pain management in spine surgery and means of assessing postoperative pain and functional outcomes. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:930-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SI, Ha KY, Oh IS. Preemptive multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain management after lumbar fusion surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Spine J 2016;25:1614-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stucky CL, Gold MS, Zhang X. Mechanisms of pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:11845-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lenart MJ, Wong K, Gupta RK, et al. The impact of peripheral nerve techniques on hospital stay following major orthopedic surgery. Pain Med 2012;13:828-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemos P, Pinto A, Morais G, et al. Patient satisfaction following day surgery. J Clin Anesth 2009;21:200-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, et al. Causes and risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions after lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:761-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wheeler M, Oderda GM, Ashburn MA, et al. Adverse events associated with postoperative opioid analgesia: a systematic review. J Pain 2002;3:159-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woolf CJ, Chong MS. Preemptive analgesia--treating postoperative pain by preventing the establishment of central sensitization. Anesth Analg 1993;77:362-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skovrlj B, Gilligan J, Cutler HS, et al. Minimally invasive procedures on the lumbar spine. World J Clin Cases 2015;3:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barbagallo GMV, Yoder E, Dettori JR, et al. Percutaneous minimally invasive versus open spine surgery in the treatment of fractures of the thoracolumbar junction: a comparative effectiveness review. Evid Based Spine Care J 2012;3:43-9. [PubMed]

- Mathiesen O, Dahl B, Thomsen BA, et al. A comprehensive multimodal pain treatment reduces opioid consumption after multilevel spine surgery. Eur Spine J 2013;22:2089-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pozek JP, Beausang D, Baratta JL, et al. The Acute to Chronic Pain Transition: Can Chronic Pain Be Prevented? Med Clin North Am 2016;100:17-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berger RA, Jacobs JJ, Meneghini RM, et al. Rapid rehabilitation and recovery with minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004.239-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rivkin A, Rivkin MA. Perioperative nonopioid agents for pain control in spinal surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014;71:1845-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bajwa SJ, Haldar R. Pain management following spinal surgeries: An appraisal of the available options. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2015;6:105-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Berger RA, et al. Upregulation of prostaglandin E2 and interleukins in the central nervous system and peripheral tissue during and after surgery in humans. Anesthesiology 2006;104:403-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ito S, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Minami T. Central and peripheral roles of prostaglandins in pain and their interactions with novel neuropeptides nociceptin and nocistatin. Neurosci Res 2001;41:299-332. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buvanendran A. Chronic postsurgical pain: are we closer to understanding the puzzle? Anesth Analg 2012;115:231-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oka Y, Murata A, Nishijima J, et al. Circulating interleukin 6 as a useful marker for predicting postoperative complications. Cytokine 1992;4:298-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cruickshank AM, Fraser WD, Burns HJ, et al. Response of serum interleukin-6 in patients undergoing elective surgery of varying severity. Clin Sci 1990;79:161-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jirarattanaphochai K, Jung S. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for postoperative pain management after lumbar spine surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurosurg Spine 2008;9:22-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sivaganesan A, Chotai S, White-Dzuro G, et al. The effect of NSAIDs on spinal fusion: a cross-disciplinary review of biochemical, animal, and human studies. Eur Spine J 2017;26:2719-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang JW, Wang CJ. Total knee arthroplasty for arthritis of the knee with extra-articular deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1769-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cottrell J, O'Connor JP. Effect of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Bone Healing. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010;3:1668-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pradhan BB, Tatsumi RL, Gallina J, et al. Ketorolac and spinal fusion: does the perioperative use of ketorolac really inhibit spinal fusion? Spine 2008;33:2079-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pandey CK, Navkar DV, Giri PJ, et al. Evaluation of the optimal preemptive dose of gabapentin for postoperative pain relief after lumbar diskectomy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2005;17:65-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan ZH, Rahimi M, Makarem J, et al. Optimal dose of pre-incision/post-incision gabapentin for pain relief following lumbar laminectomy: a randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:306-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spreng UJ, Dahl V, Raeder J. Effect of a single dose of pregabalin on post-operative pain and pre-operative anxiety in patients undergoing discectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:571-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bianconi M, Ferraro L, Traina GC, et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of ropivacaine continuous wound instillation after joint replacement surgery†. Br J Anaesth 2003;91:830-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurbet A, Bekar A, Bilgin H, et al. Pre-emptive infiltration of levobupivacaine is superior to at-closure administration in lumbar laminectomy patients. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1237-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sekar C, Rajasekaran S, Kannan R, et al. Preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief in lumbosacral spine surgeries: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J 2004;4:261-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Servicl-Kuchler D, Maldini B, Borgeat A, et al. The influence of postoperative epidural analgesia on postoperative pain and stress response after major spine surgery—a randomized controlled double blind study. Acta Clin Croat 2014;53:176-83. [PubMed]

- Singh K, Bohl DD, Ahn J, et al. Multimodal Analgesia Versus Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia for Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Procedures. Spine 2017;42:1145-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buvanendran A, Thillainathan V. Preoperative and postoperative anesthetic and analgesic techniques for minimally invasive surgery of the spine. Spine 2010;35:S274-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loftus RW, Yeager MP, Clark JA, et al. Intraoperative ketamine reduces perioperative opiate consumption in opiate-dependent patients with chronic back pain undergoing back surgery. Anesthesiology 2010;113:639-46. [PubMed]

- Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. The role of multimodal analgesia in pain management after ambulatory surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2010;23:697-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dinsmore J. Anaesthesia for elective neurosurgery. Br J Anaesth 2007;99:68-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. Postoperative pain management after ambulatory surgery: role of multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2010;28:217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet 2003;362:1921-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]