The impact of insurance coverage on access to orthopedic spine care

Introduction

Socioeconomic determinants of health have been well documented in various fields of medicine (1-5). Among them, insurance status has been shown to play a significant role in access to medical care (2,6,7). The US Census Bureau report released in 2016 reported that as many as 9.1% of the US population were uninsured, representing a total of 29 million people (8). The Patient Protection Affordable Care Act (PPACA) has expanded Medicaid eligibility with the hope of improving access to care for patients of lower socioeconomic status (7,9). The percentage of patients covered by Medicaid has increased by an estimated 6.4% over the previous 2 years (8). Healthcare policies have prioritized access to primary care and preventative medicine (10). The provisions of the act have improved Medicaid reimbursement for primary care physicians (7). Access to specialty care, particularly orthopaedic care, has not received the same attention. The amount of Medicaid accepting specialty care practitioners has decreased, with low reimbursement rates being cited as the primary reason for the trend (4,11,12). Kim et al. reported on access to upper extremity specialty orthopedic care and showed that Medicaid patients could only schedule an appointment 20% of the time compared to 89% for Medicare and 97% for Blue Cross Blue Shield (6). Medicaid has similar difficulties in getting an appointment for knee arthroplasty, and when they did obtain an appointment, they had longer waiting periods compared to Medicare or private insurance (7). Medicaid patients were found to need more referrals and have longer waiting periods in addition to fewer successful appointments for foot and ankle care when compared to Medicare and private insurance (13). Children with Medicaid insurance had limited access or no access to orthopaedic care in 38% of offices nationwide which was found to correlate with physician reimbursement rates (2).

Delayed access to care for potential spinal injury can result in severe complications (14). Lumbar disc herniations can result in neurological deficits and can be progressive and irreversible (15). Cervical myelopathy is a progressive disorder that can lead to irreversible neurologic decline (16). These patients with potentially debilitating spinal pathology cannot afford to have a prolonged wait prior to seeing a spine surgeon for evaluation. The goal of our study was to examine the relationship between insurance status and accessibility to spine care nationwide following the PPACA.

Methods

Due to the study not utilizing patient records, we received an exempt status from our Institutional Review Board. We organized a nationwide survey by searching for five offices with board certified Orthopaedic spine surgeons from each state. The search criteria “Orthopedic Spine Surgeon (State)” was used in Google Maps. A list of available practices was generated and subsequently randomized. The first five practices from the list were contacted. If a clinic was unable to be contacted, then the next office on the list was called. Each office was contacted three separate times within two weeks of the first phone call. The caller used a script stating that he was a patient with acute back, and lower extremity weakness who had initially presented to an out of state emergency department (ED) and were told that they were required to follow up with a spine surgeon. If asked, symptoms were progressing and imaging including MRI had already been performed. For the first call, the caller would state their insurance was a commercial private insurance. In the subsequent two calls, the same script was used, but the insurance provided would be Medicaid or Medicare instead of private insurance. Any appointment given was subsequently canceled so as not to interfere with the office scheduling. Timing of the appointment provided was recorded as well as the instances where practices required a primary care provider (PCP referral).

Each time an appointment was given it was recorded as a binomial event. The frequencies were then tabulated as a percentage. Statistical analysis was then performed using JMP Pro 12 (Cary, NC, USA). A Chi-square analysis between the various insurance status was then performed comparing private insurance to Medicare, private insurance to Medicaid and Medicare to Medicaid. If the frequency was <10 a Fischer exact test was used. A P value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

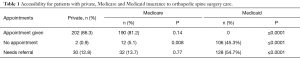

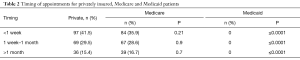

A total of 702 phone calls were made to 234 orthopedic surgery practices with spine specialty care between January and June of 2016. Each state had 5 offices that were contacted with the following exceptions: Alaska, Colorado, Indiana had 4 offices contacted; Hawaii and Vermont had 3 offices contacted. West Virginia had 2 offices contacted and North Dakota had 1 office contacted due to difficulty reaching independent board certified orthopedic surgery practices. Eighty-six percent of practices accepted the factious caller with private insurance without the need for a PCP referral and greater than 99% of practices accepted privately insured patients if a PCP referral was available to be provided (Table 1). If the caller had Medicare insurance, they were able to obtain an appointment from 81% of practices and 94.9% of practices when including those needing PCP referral. No practices offered an appointment to the caller with Medicaid insurance without a PCP referral. A total of 54.7% of practices offered an appointment to Medicaid patients with a PCP referral. If the caller had private insurance, they were able to obtain an appointment within 1 week from 41.5% of practices contacted. Those with Medicare were able to obtain an appointment within 1 week from 35.9% of practices. There was no statistically significant difference in ability to obtain an appointment with an orthopedic spine surgeon by a patient with private insurance versus one with Medicare within 1 week (P=0.21), 1 week to 1 month (P=0.9) or greater than 1 month (P=0.7). There was a significant difference in ability to obtain an appointment between a privately insured or Medicare patient and one with Medicaid at all time points (P≤0.0001). The timing for available appointments and type of insurance can be seen in Table 2.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

This study compared access to orthopaedic spine care between patients with private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid insurance. Access to care was greatest for those with private insurance followed by those with Medicare insurance. In fact, no practices that were contacted would provide Medicaid patients with an appointment without a PCP referral and even with PCP referral only 55% of offices offered an appointment. This was significantly lower when compared to privately insured and Medicare patients where only small proportion of offices required a PCP referral to obtain an appointment, 12.8% and 13.7%, respectively. These findings are consistent with a recent study that demonstrated that only 0.8% of Medicaid patients were able to obtain an appointment with a spine surgeon in a subset of states that have expanded Medicaid (17). Requiring a PCP referral prior to scheduling an appointment can improve clinic efficiency by avoiding scheduling improperly triaged patients with benign conditions. However, in patients requiring more urgent attention this can delay a patient’s ultimate care. Privately insured patients were given an appointment by 86.3% of practices and Medicare patients were given an appointment from 81.2% of practices without needed a referral. The overwhelming majority offices offered appointments earlier than one month to those with private insurance and Medicare. There was no statistical difference in the timing of appointments offered to privately insured versus Medicare patients at all time points.

As noted above, financial status, level of education and access to care have been associated with disparities in patients’ health (3,6,7,13,17). Insurance status is a significant cause for lack of care. Recent changes in healthcare policy expanded Medicaid coverage with the hopes of improving access to care for patients of low socioeconomic status (8). This study demonstrates that simply having insurance does not necessarily increase access to care, as the Medicaid patients in the study were much less likely to obtain an appointment compared to privately insured and Medicare patients.

There were several limitations in this study. Timing for appointments for Medicaid patients who required a PCP referral were not able to be obtained. As such, the authors were unable to compare appointment times between Medicaid patients with PCP referrals and privately insured/Medicare patients. Additionally, this study did not investigate access to spine care for those patients with insurance plans provided by the Affordable Care Act, which are essentially Medicaid plans administered by private insurance companies. While these plans are distinct from Medicaid, provider reimbursement is more similar to Medicaid reimbursement than that of private insurance or Medicare. Future investigation including this group of insurance would further help determine whether recent expanding insurance coverage has functionally improved access to care in this country.

In conclusion, this study evaluated access to orthopaedic spine care for patients with private insurance, Medicare and Medicaid. The results of the investigation support the authors’ hypothesis that there is a significant barrier to accessing orthopaedic spine care for patients with Medicaid insurance.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Due to the study not utilizing patient records, we received an exempt status from our Institutional Review Board.

References

- Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Collaboration. Cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes mortality burden of cardiometabolic risk factors from 1980 to 2010: a comparative risk assessment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:634-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:400-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a review of the literature. Milbank Q 1993;71:279-322. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarzkopf R, Phan DL, Hoang M, et al. Do patients with income-based insurance have access to total joint arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1083-6.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaakkimainen L, Glazier R, Barnsley J, et al. Waiting to see the specialist: patient and provider characteristics of wait times from primary to specialty care. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Wang Y, et al. The Effect of Insurance Type on Patient Access to Carpal Tunnel Release Under the Affordable Care Act. J Hand Surg Am 2016;41:503-9.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Hsiang WR, et al. The Effect of Insurance Type on Patient Access to Knee Arthroplasty and Revision under the Affordable Care Act. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1498-501. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnett JC, Vornovitsky MS. Current Population Reports, P60-257(RV), Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2016.

- Blumenthal D, Collins SR. Health care coverage under the Affordable Care Act--a progress report. N Engl J Med 2014;371:275-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Fonseca VA, et al. Surge in newly identified diabetes among medicaid patients in 2014 within medicaid expansion States under the affordable care act. Diabetes Care 2015;38:833-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinman A, Bozic KJ. Impact of payer type on resource utilization, outcomes and access to care in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008;23:9-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1673-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Roth AS, et al. Survey of Patient Insurance Status on Access to Specialty Foot and Ankle Care Under the Affordable Care Act. Foot Ankle Int 2016;37:776-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein NE. Unnecessary multiple epidural steroid injections delay surgery for massive lumbar disc: Case discussion and review. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:S383-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang HS, Nakagawa H, Mizuno J. Lumbar herniated disc presenting with cauda equina syndrome. Long-term follow-up of four cases. Surg Neurol 2000;53:100-4; discussion 105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tetreault L, Goldstein CL, Arnold P, et al. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: A Spectrum of Related Disorders Affecting the Aging Spine. Neurosurgery 2015;77 Suppl 4:S51-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anandasivam NS, Wiznia DH, Kim CY, et al. Access of Patients With Lumbar Disc Herniations to Spine Surgeons: The Effect of Insurance Type Under the Affordable Care Act. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:1179-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]